An architect needs to know the material.

We all know the rudiments of construction. There are boards with common nominal sizes of 2x4 up to 2x12 and sheets of plywood that are 4’x8’ and all of this can be thrown into an infinite number of possible configurations with nails, brads, or screws after cutting them to size with power tools. Usually this entire assembly then gets shrouded with a protective layer of gypsum board on the inside and siding or veneer on the exterior. The result is something that resembles a plaster wall on the inside and wood siding or solid brick structure from the exterior. We see these things in our homes and are satisfied that the appearance of an “authentic” home have been met, at least. This is how it is done. On the inside, the kitchen and bathrooms are equipped with cabinetry. The homeowner has many choices of door styles and drawer configurations to choose from. In custom work, the architect will design and detail the cabinetry for the owner. But what is the architect designing? Cabinetry is a box, or carcase to use a traditional term, with a door or lid. Traditionally the carcase was created by a joiner who assembled the box using dovetails, mortise and tenons, and other means of joinery. He would use materials supplied by a sawyer, who in turn gathered his stock from a woodcutter.

In the 20th century, woodcraft began to be industrialized and sawmills began to eliminate much of the labor required to process the materials needed to build. This led to standardization of the material and therefore unit sizes became more common. These increments are helpful, because it makes delivery easier and allows an individual worker to grab a board and carry it.

The built world is full of approximations of wood assemblies. Cabinetry is made of plywood or particleboard stapled into boxes matching standard dimensions, with widths usually in increments of 3” so that many of them can be made free of context so that they can be shipped to a site without customization. These boxes then may have a door fashioned from a single piece of mdf with a melamine finish baked on and with the use of a router a traditional rail and stile cabinet door may be imitated. The signature of expensive cabinetry is the drawer, which is detailed with dovetails created with a jig. A tongue and groove wainscot (which is a type of joint to allow for wood movement) is imitated with a sheet of thin plywood scored with a router to imitate its older brother. When we do encounter “real wood” in our built-world it is most likely to be preserved, amber like, beneath a thick coat of glossy polyurethane.

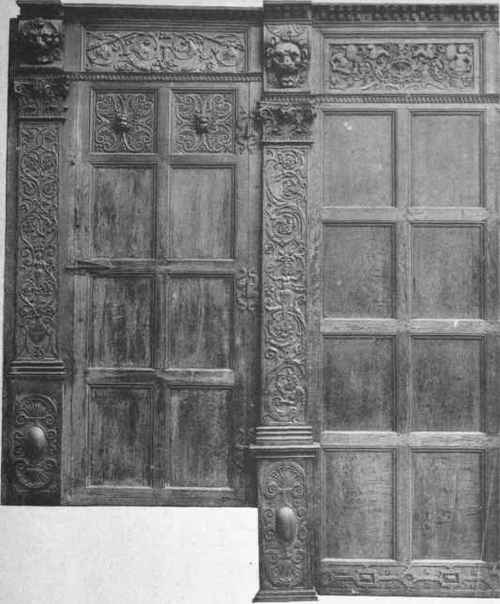

The result of this innovation is at the true reason behind why a joint is used and why a panel in a wainscot is of a certain proportion is lost to the architect. If a sheet of plywood is a stable material, then a wainscot can be detailed 4’-0” wide, rather than the width of the board cut from a tree. The look of “real” wainscot then can be approximated by applying factory made moldings to create a raised panel. In traditional English joinery, the wainscot is created with rails and stiles that are joined with mortise and tenon joints. The panel is inserted and held in place with a beaded rabbet on three sides and the bottom rail is planed to have a sloping top. This is to represent an ashlar stone detail, which the wood wall is meant to represent. The method of joinery used allows for movement in the wood without longterm damage to the paneling. There is a reason for each decision: the direction of the grain, the orientation of the rings to face in or out, the width and spacing of the panels – this list can go on.

By contrast, if what one has at hand are dimensional, manufactured materials and wishes to represent a traditional wall of paneling, then the result can begin to stray unintentionally from the original that is the inspiration become a distorted, distant approximation.

A sheet of plywood should not be the basis of good design.

With Know-how, to quote Louis Sullivan, “Form ever follows Function.”